How Blue Systems Leveraged the Databricks Ecosystem to Quickly Go to Market

This article was originally published on Medium. Read the original here.

In a fast-moving world where shared usage is replacing ownership, flow optimization and curb infrastructure access management are the main challenges faced by the cities of tomorrow.

Blue Systems was established several years ago as a smart city startup within the Bolloré Group. Blue Systems mission is to help cities around the globe to speed up the transition to sustainable mobility, by providing state-of-the-art smart mobility and smart city software solutions. Today, Blue Systems Smart City Platform is deployed in many cities in the US and Europe, connecting over 100,000 vehicles and devices and processing over 3 million trips daily.

This industry is moving fast, and we need to be able to quickly go to market when a new opportunity arises. In this post, we will detail how we have successfully built a new service from the ground up in a little less than a month, leveraging the Databricks Lakehouse Platform, which unifies Datalake, SQL Warehousing, and API capabilities.

Use Case: Dynamic Parking Quote API

We made this Proof-of-Concept work for a city which we will call "Wellparkedcity".

Wellparkedcity uses about 140 Pay and Display (PnD) parking ticket machines to manage on-street parking. Additionally, over 200 parking bay sensors are installed along some of the streets, which collect utilisation and compliance data.

Wellparkedcity seeks to implement some advanced parking management techniques. One such technique is the use of dynamic parking. Blue Systems' goal was to build a system where parking ticket machines are able to send a request for pricing and get a quote back. And this quote was supposed to be based on complex pricing logic, and affected by the current, real-time occupancy.

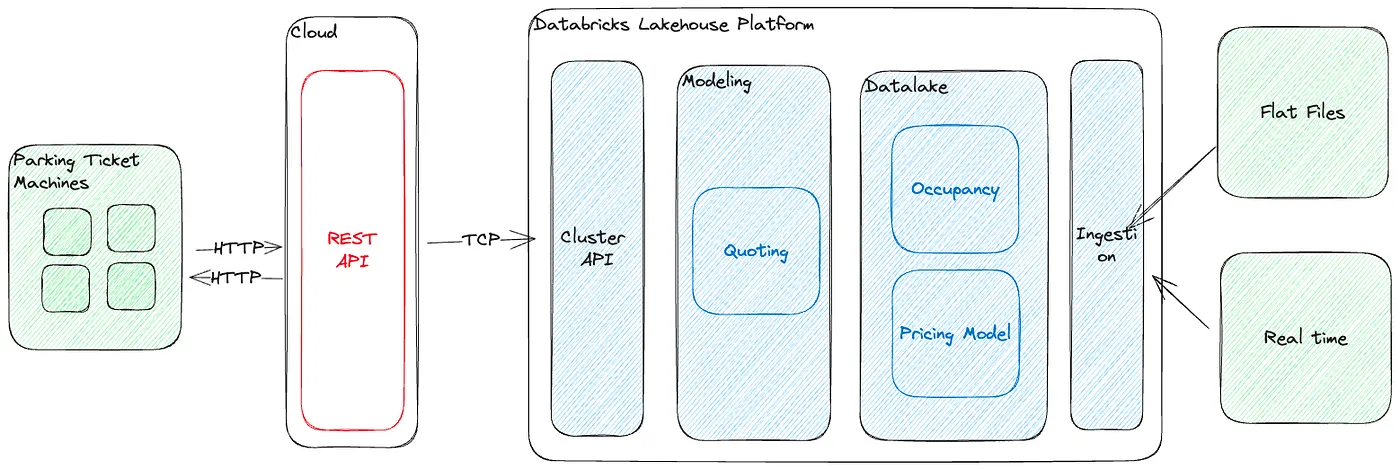

Here is how the infrastructure looks like at a glance.

Let's go into more details for each component. I will finish each section by summarizing what we had to do and how we did it.

Pricing Model

Wellparkedcity already employs a complex pricing system, which varies by street and seasonality. Here is an example pricing for a given street, at a given point in time:

- 8AM - 11AM: 1 hour free then 3.00 per hour

- ...

- 7PM - 8PM: 1 hour free then 1.70 per hour

We had to 1) Ingest the reference pricing data, which was done by easily loading reference CSVs into Delta tables via the Data Ingestion features and 2) Implement the pricing experts system, which we modelled on SQL.

Occupancy

Wellparkedcity collects data from its sensors and obviously from ticketing (when a user pays for parking). Not all parking spaces are equipped with sensors and occupancy data is unreliable across the inventory. Therefore, a hybrid model is needed where:

- Whenever sensor data is available it is used,

- Otherwise a theoretical occupancy model based on historical data is used.

Given we know when vehicles request parking and for how long, we can project a theoretical load by assuming that the vehicles stay for a fraction of the full duration. The fraction is determined by looking at historical data.

We had to 1) Determine the historical load factor and statistical duration factor and 2) Create a model that outputs the instantaneous load, both of which were modelled on SQL.

The last step would be to continuously ingest sensor data, which is easily done via Databricks Autoloader and Delta Live Table.

Requests (Quoting)

When a driver goes to the parking automaton to retrieve their ticket, the automaton has to send a request to the central server to fetch a pricing quote. A request will contain the following parameters:

- The timestamp at which the request is made. Example: "2022-07-01T18:00:00Z"

- The requested parking duration. Example: "5400" (seconds)

- The parking space that is requested. Example: "XGPCT-30"

A response will contain what price the automaton is supposed to quote for this driver. A response will look like:

{

"id": "744e79ca-bb32-4f58-b05b-e87a970c6a12",

"curb_space_id": "XGPCT-30",

"timestamp": "2022-07-01T18:00:00Z",

"duration": 5400,

"parking_starts_at": "2022-07-01T18:00:00Z",

"parking_ends_at": "2022-07-01T19:30:00Z",

"amount": 247, // In minor units, eg 247 for 2.47EUR

"currency": "EUR"

}

We had to develop an API that receives requests from automatons, connects to our model to fetch quotes, and serves them back to the automatons, which we did by 1) hosting a Golang API on AWS, deployed with SAM and 2) connecting it to a Databricks SQL Warehouse cluster.

Comments on Modelling in SQL

We could have modelled the expert pricing system in API land, i.e., in Golang or Python. However, we tend to promote a "data-first" approach. This has a couple of advantages:

- Faster feedback loops while iterating.

- Being able to test on historical data easily

- Stateless algorithm

The only drawback is that this comes at a slight performance loss, which is not significant in a real-world scenario. For instance, using the current implementation, we are getting response times below 300ms, which is plenty acceptable for the given use case. The algorithm can always be rewritten later on if performance becomes a concern, although in >90% of cases this won't be needed.

Faster feedback loops

In API land, testing while developing usually involves extra steps depending on which development practices you're employing. For instance, you might require mocks to substitute infrastructure components (if you're really going the wrong way about it you may even have to spin up containers...), or the calculations will involve state, which makes it harder to figure out what's happening in complex multi-stages algorithms. Usually this involves injecting console log statements all over the code, which you have to remove at some point before going to Prod.

SQL being declarative and fully introspectable, it is easier to follow and prototype with it.

For example, at some point we had the following SQL statement:

WITH api_request AS (

SELECT

UUID() AS request_id,

CAST('2022-07-01 17:00:00' AS TIMESTAMP) AS timestamp,

INTERVAL '02:10:00' HOUR TO SECOND AS duration,

'XXXXX' AS curb_space_id

UNION

SELECT

UUID() AS request_id,

CAST('2022-07-01 18:00:00' AS TIMESTAMP) AS timestamp,

INTERVAL '00:30:00' HOUR TO SECOND AS duration,

'YYYYY' AS curb_space_id

),

parking_request_interval AS ( ... ),

parking_request_segment AS ( ... ),

latest_tariff AS ( ... ),

meter_area AS ( ... ),

latest_area_occupancy_timestamp AS ( ... ),

latest_area_occupancy AS ( ... ),

overlapping_program AS ( ... ),

debug AS (

// Output you would want to see while debugging

),

final AS ( ... )

SELECT

*

FROM

debug

It's very easy to simply SELECT * FROM any of the CTEs to inspect intermediary states and apply fixes, then rerun within the same second.

You can also see that we're using a couple of Databricks SQL features, such as SELECT without FROM to create 1-row tables to simulate requests, and both SELECT * EXCEPT () and GROUP BY ALL which are really handy.

All-in-all, this provides a great developer experience.

Being able to test on historical data easily

The SQL statement above will work both for a single request, or for a full table of requests, because it's a set-based approach as opposed to a row-wise (loop) approach. We get this by virtue of using SQL and the correct GROUP BYs. This can be helpful to assess how the model is doing against historical data. Again, while this is a trivial operation here with SQL, this might involve additional scripting in API land.

Conclusion

In this post, we covered how we were able to build a complex, fully operational system in less than a month, involving data ingestion, modeling, and API servicing, earning us the favors of a new business partner.

The unification of all the engineering layers on the Databricks Lakehouse Platform allows unparalleled speed in prototyping solutions. Moreover, going from prototype to production is also made easy because each component of the stack is scalable.

The different Databricks features that were used were:

- Datalake, to store all the data

- Data Ingestion, to ingest reference files

- SQL Warehouse, with Serverless: Modelling, to derive analytics and model complex systems

- SQL Warehouse, with Serverless: Cluster API, to expose the model to the outside world (our Go API)

- Delta Live Table: To continuously ingest data

- Unity Catalog: To manage multiple deployment environments

Learn more about the Databricks Data Intelligence Platform: Digital Native Business and Applications | Databricks